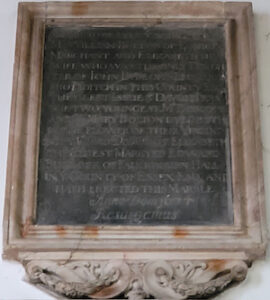

Monuments

St Andrew’s, Enfield is deemed to have the finest collection of monuments outside of a Cathedral in Britain. Our incredible range of monuments chart a social history from ancient aristocrats, royalty and nobility, through post-Reformation merchants, influential politicians, Lord Mayors of London, pioneering medical professionals, to World War One heroes killed in action – and much more.

Our aim is to complete full research on each monument and make that information available on this website and in other formats. You will appreciate that this is a large piece of work that will take time to complete. We are grateful to our historian, Robin Barden, for providing the information on these pages. Robin’s is an ongoing research project, and we will be adding more information on a regular basis. So please do check back regularly for more information.

Listed below are the monuments in the church building at St. Andrew’s. As the page develops, we will create a link to a separate page for each monument, with full written historical detail and a short video about it. Please bear with us as we create and upload this information.

You can also find a curated list of information about the monuments here. However, please be aware that this is being constantly updated and is not yet complete.

A brief social history

The oldest monument in St Andrew’s, the tomb of Lady Jocosa, was built in the dying days of a manorial system that had dominated local English life for over 600 years. However, this tomb reminds us that it wasn’t dead yet.

The influence and profitability of a manor may have waned significantly, but it could still lay claim to sufficient status and income. The inscription on Jocosa’s tomb makes sure to highlight her claim to estates which stretched across the English counties of Sussex, Surrey, Southwark, Hampshire, and Nottinghamshire.

But it would not last long. Following the bloodletting in the War of the Roses and the impoverishment by Henry VII of those nobles that remained, the movement of power away from the local Lords and towards the national institutions of the King’s court and government accelerated with such force that the manorial system was swept aside.

But the impoverishing of barons and the abolishment of the manorial system did not mean the end of nobility in England. Indeed, the narrative depicted on the arch above Lady Jocosa’s tomb depicts the story of how a minor family of no notable lineage – the Manners – established themselves in the upper echelons of society out of the ashes of the noble families Tiptoft and Roos.

This shift was caught up in interlinked political, cultural, and economic changes. These changes included an expanded role for local government, accountable to an increasingly centralised government; a shift in the relationship between Lord and tenant from a personal encounter to a more contractual association; and the drive to enclose parcels of common and other land into larger, privately held, landholdings.

In St Andrew’s, we also see the presence of another economic development which both impacted and benefited from this significant shift in the social fabric of local life – the rise of the city merchant.

Changing economic conditions and technological developments had enabled merchants to make increasingly large fortunes since the 14th-century. But within the older structures of society, merchants were a lowly profession far removed from noble lords in their manors and barons on the battlefield. However, in this quickly changing world the merchant’s money would start to talk; enabling him to rise to the very top of local, if not national, life.

The monument to Benjamin Deicrowe is a good example of how this change, which was to accelerate in the 17th- and 18th-centuries, had already started in the 16th-. The monument is telling for its unashamed declaration of Benjamin’s association with the City of London that leaves the viewer in no doubt that the charitable behaviour which marked him out as part of the gentry came not from a long lineage of noble families who had amassed vast wealth through the operation of multiple manors, but from the buying and selling of goods.

This new ability to obtain the differentiation and status of a noble gentleman through the correct consumption of wealth is further observed in the intimate connection between Sir Nicholas Raynton’s monument and the inheritance of Forty Hall. This was a manor house that was not part of any inheritance he was due as the third son of Lincolnshire farmers, but one he himself built with the fortunes he amassed by trading in fine cloth from Italy.

The Bolton monument provides a variation on this theme, glossing over the fortuitous use of the monies they had made in the city to offer a mortgage against that very status of gentility, the manor, which by ‘calling in’, they were able to acquire for themselves along with all its associated status.

The monuments to Charles Rich, Richard Fountaine, and Hinde Pyke affirm that similar claims to gentility through the appropriation of noble signifiers, such as charitable giving, continued well into the 18th-century. Unlike Charles and Richard however, Hinde did not make her money via the city but, it appears, was a beneficiary of her late husband’s dubious financial affairs.

Hinde’s monument also reflects the emergence of the nuclear family, that we see first with the monument to Martha Palmere. The foregrounding of inheritance we find on the monument of Lady Jocosa is replaced by the language of personal grief at the loss of a wife and mother. But while this ‘emotional turn’ may resonate with the modern ear, the way Martha is framed by both the inscription and the style of the monument itself is more problematic. Here the ‘role’ of wife and mother is exalted to impossible heights, setting up Martha, but also all women, as such virtues of goodness that no space is allowed for any other aspects of female identity. At the same time, the onlooker is reminded that even exalted as it is, this identity is itself always subservient to a women’s framing by her husband and father.

Similarly, the monument to Elizabeth Grene. Indeed, we would struggle to find an alternative female voice on such a public artefact as a monument. But we are fortunate to have access to the works and story of Lady Mary Wrothe through the coffin plate of her son, James.

Historical documents and photos

Do you have any historical documents or photos relating to St. Andrew’s? Would you be willing to share these on our website? If so, we would love to hear from you! Please email Rev Dr Steve at steve.griffiths@london.anglican.org. Thank you.